- Home

- Eleanor Wilton

To Teach the Admiring Multitude Page 4

To Teach the Admiring Multitude Read online

Page 4

The Colonel exhaled impatiently, replied with conviction. “She is no unknown, obscure girl for Darcy.”

“How well can he be acquainted with her, Henry?” Lady Richmond inquired evenly, hoping to ease the rising tension. She disliked a scene above all other things. “He has never spoken of her before; we have never heard mention of this young lady or her family until this letter announcing his engagement. It is all exceedingly peculiar.”

“It is hardly surprising that he should keep his intentions private; it is entirely in keeping with his character. Regardless, he first made her acquaintance more than a full twelfth month ago, Mother. They have been in each other’s company in quite varied society, including at Rosings Park.”

“This is all irrelevant,” the Earl barked impatiently. “The pertinent point is that Darcy is master of one of the finest estates in Derbyshire and my nephew. Is he truly to align himself to a girl of no family and no fortune? A young lady who is in every way beneath him? It is shameful!”

“Father, the pertinent point is precisely that Darcy is his own master and can therefore marry whomever he chooses. He wants neither position nor fortune and is entirely free to act in accordance with his wishes. I must be allowed to insist, sir; there is nothing shameful in his choice. Miss Bennet is a gentleman’s daughter.”

“I have heard from Lady Catherine as well, Henry. I am informed that the young lady’s connections on her mother’s side are hardly desir-able. She has an uncle in trade, another who is a common country solicitor. What is more, her sister is married to the son of Darcy’s father’s steward; that very same rapscallion your uncle so inexplicably doted upon. Such a connection! If she lived, my sister would have been profoundly affronted by such a disgraceful alliance.”

The Colonel had no defence to offer against the bride’s inferior connections, and so simply reiterated his praise of the young lady herself. “Darcy is perfectly aware of her situation. Miss Bennet herself is a superior young lady.”

“Your cousin Anne is not?”

The Colonel could not disguise the look of exasperation that passed over his generally amiable countenance. “Must we begin with this nonsense afresh?”

“I fail to comprehend how the tacit engagement between your cousins is nonsense,” cried the Earl forcefully.

“Darcy has long made it very clear he recognized no obligation, whatever the desires of the family. He had no promise to honour with my cousin,” returned the Colonel with equal force.

“I concede there has been no formal engagement, no obligation. It was not, however, an unreasonable expectation to anticipate that he would satisfy the hopes of my sister and the wishes of his mother. Indeed, it should have been an ideal alliance.”

“The notion of Darcy married to Anne has always been ridiculous. Impractical as well.”

“Impractical?” the Earl inquired with a furrowed brow. “What fresh absurdity is this?”

“I doubt very much that Darcy would have fathered an heir in such a marriage, which is, after all, no unimportant purpose of marriage.”

“He rather has a point, Father,” Edward joined in with a cynical laugh. “Duty can only take a man so far, and then Anne is such a weak, sickly thing she might not be capable of bearing a child.”

“Truly, gentlemen!” Lady Richmond cried. “A little compassion towards your poor cousin would not be ill advised. The principal point remains this Miss Bennet and this reckless, hasty engagement.”

“Call it what you will, Mother, but it is anything but hasty,” the Colonel insisted. “Many an engagement has been established on far less familiarity than my cousin can claim with Miss Bennet. Has not Edward secured the hand of Lady Patience Faircloth though they are no more than passing acquaintances? Perhaps it would be better to inquire if Father has not yet secured him her hand?”

“Your tone is not appreciated, Henry,” the Earl scolded. “Your cousin would have done well to have followed Edward’s example.”

“I believe, sir, Darcy has made the better choice. He will not need be concerned with dullness, frivolity and empty vanity in his wife.”

“You will not speak of her in such terms,” Edward interjected in defence of his anticipated bride. “Lady Patience Faircloth is from an old and noble family. She is a fine lady.”

“A pity neither her person nor her character are as appealing as her dowry. Our cousin will not need depend upon such cold comforts in his marriage.”

“What will he have that is so very valuable? His wife’s impressive family guests at Pemberley?” Edward disdainfully inquired.

“He shall have what you never shall with Lady Patience. Happiness, dear brother, happiness.”

“Happiness?” the Earl inquired in disbelief. “Why, what a romantic notion! I never suspected my hardened army son to be so soft in the belly. Happiness is fleeting. Fortunes and connections are not. Mark my words, son, your brother’s course will prove the wiser. Darcy will find this precious happiness purchased at a very high cost when he inevitably realizes it wanting in durability. He will rue the day he entered into this engagement,” he added with finality. With that the topic had been dropped from conversation and the prevailing animosity towards the union allowed to stand.

A few days later Mr. Darcy had returned to London to arrange the marriage settlement and had called on his uncle and aunt whilst in town. The results had been less than favourable. He had been greeted in the principal drawing room of Richmond House with an antagonism not common between them, for the two families had always been closely aligned, a connection further strengthened after the death of Mr. Darcy’s father.

“Darcy, my boy, you cannot expect me to congratulate you on such a marriage,” Lord Richmond had declared frankly and with little preamble.

Darcy had stiffened completely; his chin immediately lifted in anger and offense. “I do not believe it unreasonable to expect you should offer me a sincere wish for my happiness.”

“Happiness! That word again!” Lord Richmond had intoned cynically. “What has marriage to do with happiness? What is this modern notion? Marriage is not a sentimental amusement designed to satisfy mere personal longings; it is a serious business, the foundation of a properly regulated society. You cannot imagine that I should approve this heedless choice you have made. Your mother would have been very displeased. Abandoning Anne to uncertain prospects for some inconsequential girl with no connection to our family or our interests. I should have never expected it of you.”

“Sir!” Darcy had intoned in that distinctly Darcy tone of controlled, cold dismissal. “I will not permit myself to be accused of abandonment. My cousin had no claim upon my honour. I have made my choice. Miss Bennet is to be my wife and you can justly comprehend that I will not abide from any person, even from your lordship, disrespect towards her person. You have made your sentiments clear and I will not demean myself or Miss Bennet by remaining to hear further censure of our union.”

Lady Richmond interjected with composure. “Darcy, you must understand, we are merely concerned for your interests and for Georgiana’s. Setting Anne aside, this marriage is entirely opposed to your interests. You cannot refute that Miss Bennet brings nothing to the marriage but her charms.”

“I comprehend your surprise at my choice,” he conceded. “However, I would have anticipated that you had sufficient trust in my criteria and wish for my happiness to welcome Miss Bennet without such pre-emptive censure. For the sake of the excellent relations between our families, if nothing else, I expected a modicum of liberality. You must now excuse me, I will not remain to hear continued disparagement of my future wife and marriage.”

“Darcy!” Lord Richmond had called out as his nephew made to exit the room. “Do not depart on such unhappy terms. You are my dear sister’s only son, my godson, understand that I wish only what is best for you.”

“Miss Bennet is precisely that.”

“I can only hope she will prove to be so,” Lord Richmond had responded with reluctant a

cquiescence.

Had any other person spoken to him in such terms Mr. Darcy would have departed without another word, indeed would not have remained for such a distasteful exchange. He paused now in honour of the essential familial anchor Lord and Lady Richmond had for many years provided to both himself and Georgiana. He controlled his ire and disappointment in deference to the good will that had long subsisted between them. “I return to Hertfordshire tomorrow. My marriage is to take place in four weeks’ time, on the first of December. I can only hope that when that day arrives you will have set aside your disapproval. It would be more than unfortunate to be estranged, but I will have no cause to repine my choice.”

When Darcy departed thereafter with a curt and cold, “good day,” Colonel Fitzwilliam had turned to his parents to encourage a warmer acquiescence, but his father had quit the room as quickly as Darcy, dismayed and vexed.

“Mother!” the Colonel cried with exasperation. “You must convince Father to accept this marriage with more generosity.”

“I will do no such thing. I concur with your father entirely. This engagement is a degradation.”

“You must learn to think of it otherwise. She is to be his wife and his first loyalty will naturally be with her. The family must accept her. Darcy will walk away from anyone who does not; where Darcy goes Georgiana follows. You must see that, Mother. He has asked me to be witness to his marriage and I have every intention of so doing. We have lost Alice; must you lose Darcy and Georgiana as well? I most assuredly will not.”

The Colonel’s stark admonition troubled Lady Richmond, and when she spoke again her voice had a vaguely diffident tone. “Such connections, Henry; such insignificant, unfortunate connections. What of her entire lack of fortune? Her father’s modest little estate is entailed away from the female line; should he die tomorrow she and all her family could be immediately turned out of their home. I cannot fault a young lady in such a precarious situation for seeking security, but for this very reason how can Darcy be sure she is not a common fortune hunter? Passion is an extraordinarily adept disabler of a gentleman’s reasoned judgement.”

“Darcy has confided to me certain episodes between them which I am not at liberty to discuss but which plainly demonstrate that she did not accept him for the pecuniary reasons so many have sought to secure him. I have myself been witness to sufficient interactions between them to perceive she was not, as have been so many young ladies of his acquaintance, ready for his command, if you will. Trust me, Mother. Whatever your concern regarding her situation, you can be entirely assured that she herself is of unimpeachable character.”

As Lady Richmond watched the expression of earnest determination spread across her son’s face a sudden and unwelcome suspicion was born. “You admire her very much yourself, Henry.”

“I do. She is delightful. I believe unequivocally that my cousin has chosen well for himself and for Georgiana, her admittedly inferior connections notwithstanding.”

“I confess I grow quite curious to become acquainted with this remarkable creature,” she responded derisively. “She has charmed you both completely out of all reason. Perhaps Lady Catherine has not mistakenly declaimed her arts and allurements?”

“I do not wish to create false expectations. She is no Glencora Morris, if that is what you are thinking, Mother. Quite the opposite! She is simply a charming, amiable, intelligent and principled young lady.”

“That is hardly an encouraging testimonial. The world is filled with charming, amiable young ladies far more favourably situated, Henry.”

The Colonel considered for a moment in silence, doubting how to reach the goodness within his mother, that portion of her heart that hoped only for the happiness of those she cared for, that portion of her mind that understood the sometimes heartrending constrictions forced upon a person’s wishes by society’s peculiar and often unbending demands. He looked upon his mother’s face and recognized the wisp of loneliness, of sadness, quite distinct from their topic of conversation. He walked to her side and took her hands into his own. “Promise me this, Mother; when you make her acquaintance you will give her a fair opportunity. For your own sake as well as Darcy’s. You may find in her that sensible and warm female companionship that you have lacked since dear Alice passed, which Edith is incapable of giving and for which your sons have thus far failed to provide any recompense.”

Lady Richmond had thought her son strangely and surprisingly sentimental in his judgement, but there was nothing to be done. Whilst none had been as violent in disapprobation as Lady Catherine, all had doubted the sagacity of Mr. Darcy’s choice, and none had been warm—excepting Henry. For Georgiana’s approbation could hardly be considered—she so revered her brother that she was incapable of standing in opposition of his wishes or of holding a contrary point of view.

After Mr. Darcy’s visit to his uncle not another word had been exchanged between them until the coldly civil congratulations delivered on the morning of his wedding. Lady Richmond was ashamed. He had deserved more kindness and she was now eager to become acquainted with the young lady who had provoked such a rare rift amongst the members of the Fitzwilliam and Darcy families. Thursday could not arrive rapidly enough for her satisfaction.

Chapter 6

Dinner at Grosvenor Square

Mr. Darcy was not accustomed to the feelings of uneasiness and anticipation with which he was dressing for dinner at Lord and Lady Richmond’s. It was disconcerting. He had infrequently felt such a desire for approbation—indeed he had more likely felt himself above either the censure or approbation of others. Yet he understood it was not for his own sake that he felt such anxiety, but for his wife. He could not forget, nor did he wish to forget, how he had once arrogantly dismissed all outside of his family circle as being unworthy of note or esteem. He understood that his family would welcome his wife with the same cold, correct politeness that had once been his own chosen method of aloof civility towards those he considered beneath him. He was agitated, and vaguely understood that it was not for her sake entirely, for he was cognizant that his family’s reception of her would be an uncomfortable reflection of his own past errors.

With neither his sister Georgiana nor his cousin Colonel Fitzwilliam present, there was none whose kindness and amiability could be entirely depended upon. It was a painful recognition—for all he had once faulted her relations, he wondered now if his would be equal to the moment. His was not a large family circle, but it had always been unified and harmonious. Family was of great importance to him and had long been his bedrock. Yet for all that, he did not require their approbation for his happiness. He did, however, wish for it.

When he and Elizabeth were newly engaged and he had come into London for a few days to see to the marriage settlement, he had called on his uncle anticipating, if not an enthusiastic blessing of his choice, at least a sincere wish for his happiness. The firm animosity and reluctant acquiescence he encountered instead had both angered and dismayed him. He had expected more understanding. When he had returned to Longbourn, Elizabeth had quickly comprehended that news of their engagement had not been received with the cordiality he had hoped for, had surmised the disappointment of his expectations.

“I am sorry I am unable to give a favourable report of my conversation with my uncle,” he had said to her, without elaborating on the precise sentiments expressed. “You deserve more.”

They had been sitting alone in a small, rarely used sitting room at Longbourn where they sometimes went to retreat from the boisterousness of Mrs. Bennet’s parlour. The steady rain falling outside encouraged the depression of his spirits. Elizabeth had reached over, taken his hand within her own and spoken sympathetically. “Do not be troubled for my sake. Your family do not know me and owe me nothing. But you do deserve more consideration, and I am sorry for your disappointment.”

He had made no reply, only lifted her hand and kissed it, admiring her lack of petty resentment, treasuring her kind consideration of his feelings.

/> Now his uncle and aunt were at last to make her acquaintance he wished for that approbation more strongly than he would have anticipated; now she was to be subject to the haughty judgement of his family he was resentful primarily on her behalf. Regardless of what he felt was due to her as his wife, he was principally resentful that this worthy, charming woman would not be simply welcomed without equivocality. Still, with regret he acknowledged he could not fault them without hypocrisy.

His valet returned into the dressing chamber and handed Mr. Darcy a box. “Sir, a lovely piece, if I may.”

“Yes, thank you,” Mr. Darcy replied distractedly as he took the box into his hands.

“Will there be anything else, sir?”

“No, that will be all, Hewitt.” He turned and walked across the room, into the master chambers and to the door of his wife’s dressing room. He stopped, lifted his hand ready to knock and paused.

“Must you always knock, darling?” Elizabeth had asked on the previous evening. He had responded with confusion, stammered clumsily something about not wishing to presume. Laughing she had placed her arms around his neck. “Such a scrupulous formality between us will not do. You must comprehend, I would not have married you if I did not desire your company.”

“You utterly bewitching creature,” he had responded with a deep chuckle, abandoning the scrupulous formality she had lamented and sweeping her into his arms and into bed without further overture.

Now, as he placed his hand on the knob and simply opened the door, walking unannounced into her dressing room, he felt a thrill as profound and bracing as that moment when he had walked into her rooms on the first night of their marriage. She had rightly laughed at him, he thought, on the prior evening, for could there be anything more natural than simply walking into her room? Yet he was unexpectedly moved, almost foolishly so, to walk in and see her sitting at her dressing table, fretting with a curl that would not stay in the binding of her pins as her maid assured her that it was becoming and coquettish as it was. But he could not so easily surrender his long-established formality, and he was awkward if not apologetic as he crossed the room and sat on the chaise.

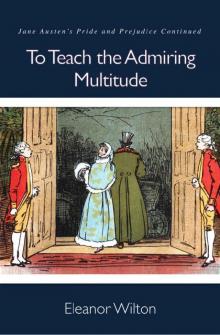

To Teach the Admiring Multitude

To Teach the Admiring Multitude